Internet Use and Economic Development: Evidence and Policy Implications Assignment Sample

Introduction

In this dissertation, four different economic development outcomes from 202 nations are examined by our Economics assignment help during an eleven-year period, from 1996 to 2007, to determine the effects of Internet use on economic development. Panel data and panel data estimate methods are used. The main theory being examined is that rising Internet usage has a beneficial impact on the following development outcomes: GDP, exports, the growth of local equity markets, and overall welfare as assessed by the UN Human Development Index (HDI). However, depending on the country's income level, Internet use has different effects on economies. Compared to low- or high-income countries, the effect is probably more pronounced in middle-income countries. This may be partially attributed to the low adoption of the Internet in low-income nations and the declining marginal product of Internet use in developed nations.

Therefore, in order to construct the four samples of interest—the whole sample of all nations and samples for each income category—countries are grouped according to the World Bank's definition of income class. To investigate the effects of extra Internet use at various developmental stages, the effectiveness of Internet use is assessed on each sample, and the findings are compared. A production function framework with Internet usage as an additional input will be used for the econometric analysis.

As important a development in human history as the invention of the printing press may have been the rise and expansion of the Internet, a global network of computing resources. The way we communicate, conduct business, learn, and govern ourselves has been permanently altered by widespread and consistent access to the world's collective computer resources and Internet-enabled gadgets. The effects of the Internet on the economy are astounding. By lowering transaction and search costs and improving access to information about goods and services offered in domestic and global marketplaces, internet use improves market efficiency. Innovation is sparked by information access, which also makes it simpler to embrace new technology and boosts output.

There are numerous stories in the news about how technological advancements are altering how business is done in the developing countries. The evidence of the effects of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) on economic growth abounds, and the possibilities seem limitless. From farmers in Kenya using cell phones for Internet access connecting with insurance agents to protect their crops (DAWN Media Group 2009), to Chinese Internet centers for remote villages (Fong 2009), to Indian fishermen using cell phones to locate markets with the greatest demand for their products (Jensen 2007), the examples of ICT's effects on economic growth are numerous.

As people and organizations use the Internet more frequently in developing economies' private and public sectors, this opens up potential for the development of new goods and services. In the end, more information availability leads to market transformation, where new markets may appear and current markets may change, enlarging their size, sphere of influence, and interacting with markets in other nations or regions. Internet access has the immense potential to revolutionize governance through information use, a prospect that plainly disturbs autocratic leaders because they promptly halt Internet access at times of popular disturbance, as was the case during the unrest in the Arab world in early 2011.

.png)

Figure 1 shows how quickly the Internet has expanded and become available to users all around the world in the past 15 years. Computers with network capabilities are now commonplace in offices, homes, and educational institutions all throughout the developed world. Almost every element of industrialised economies has been impacted by computers and the Internet. Similar to electrical electricity, municipal water, and public roads, Internet connectivity is increasingly seen by the populace in industrialised nations as a basic service. Internet access is widely available, dependable, and, for the most part, affordable. Both locals and visitors may anticipate being able to access the Internet on a regular basis, just like they do with power outlets, contemporary transportation options, and sanitary services.

If it is available at all, Internet connection in a substantial portion of the developing world is only found in densely populated areas. Only as improvements are made to the necessary electrical power and communication infrastructures is it becoming more generally available to connect to the global communication networks that permit Internet use in less developed countries (LDCs). It is difficult to connect to the Internet without restrictions without a wide range of electrical and communication resources. However, without access to this technology, the potential of the Internet to boost productivity and human welfare cannot be realised. The population's access to and affordability of computers and other devices with Internet capabilities is necessary for the Internet to have a materially positive impact on the economy.

In LDCs, political and social structures are frequently unstable, and incomes are insufficient to support the investment required to establish even the most fundamental reliable public utilities. Poor yet stable nations cannot maintain the infrastructure necessary to provide broad Internet access. In a developing nation, solid political and social structures, fundamental public utilities like the distribution of electricity, and educational resources are more basic requirements, while Internet use is a higher order need, according to psychologist Abraham Maslow (1943). Internet connectivity will not be a top priority, if it is even possible, in nations where the populace must prioritise basic survival owing to extreme poverty, a lack of or failure of public health institutions, an ongoing violent conflict, or generally unstable political systems.

The "One Laptop Per Child" initiative's underwhelming results in LDCs offer some anecdotal evidence of the inadequacy of technical solutions to produce replicable and significant benefits in nations lacking the requisite infrastructure and fundamental political, social, and economic institutions (Shaikh 2009). Of course, those who lack access to the Internet or who are illiterate will find little use in the information supplied there. This dissertation offers empirical proof that expanding access to and utilisation of the information and knowledge made available by Internet connectivity has a significant positive impact on development outcomes, and it shows how the size of this impact varies for economies at various stages of development.

In the literature on economic development, there is little empirical research on how Internet use affects development outcomes. The few studies that have been conducted on the topic have narrowly concentrated on either income growth or the productivity of a specific industry. However, economic development encompasses much more than just income growth rate. The goal of this dissertation is to empirically examine how using the Internet affects a variety of developmental outcomes. The literature is summarised in Section 2 along with a description of the research hole that this dissertation fills. There has not yet been a thorough empirical investigation of the potential productivity-enhancing effects of the global improvements in information dissemination that the Internet offers, particularly in LDCs.

In this research, I offer a straightforward theoretical framework for examining how Internet use affects economic growth. I then apply the model to a panel of data on numerous nations at various stages of development. ICT studies in the past have focused solely on growth effects, but development encompasses more than just GDP growth. By extending the scope of development outcomes evaluated, this study offers a more thorough understanding of how Internet use affects development.

Additionally, earlier research frequently makes use of dynamics-impervious cross-country regression approaches. I employ panel data and econometric estimators that can take into account dynamics and unexplained heterogeneity in this analysis. As a robustness test, I additionally estimate the models using mixture modelling methods. Studies already conducted on the effects of ICT on all countries or just one particular country presume linear responses. This is unlikely to be the case because, as was mentioned before, the ability to use and benefit from Internet use may vary according to the level of development. As a result, I divide the world into different income classes and take into account the effects on each class.

202 countries' worth of data from the World Bank, the International Telecommunication Union, and the United Nations are combined to create a rich data set for the econometric analysis using dynamic panel estimation techniques. These data cover the years 1996 to 2007 and come from a variety of sources. The analysis shows that in nations with sufficiently high income levels, Internet use has a considerable positive and possibly incidental impact on a number of development indicators. GDP, export revenues, and equity market capitalization per capita are the development outcomes taken into account in this research. A full examination of economic development must take this measure of economic production into account. Per capita GDP is maybe the most popular development outcome metric in the development literature.

Some significant studies on ICT and exports may be found in the literature on development and growth. To other development outcomes, there isn't much extension, though. By examining the connection between the Internet and exports using a model that accounts for dynamics, this dissertation expands on existing research. The comparison and assessment of the findings are presented in Chapter 5. A growing body of research on domestic financial markets and economic development has raised development financing as its main focus. This dissertation adds to that body of work by examining how Internet use affects domestic financial markets. It specifically looks into the connection between Internet usage and capitalization rates of domestic financial markets, which is undoubtedly a sign of how far along these markets are.

The United Nations Human Development Index (HDI) is used as a supplementary indicator of economic development in order to examine how Internet use affects a broader measure of societal well-being. The HDI is used in this study, as well as many others, as a stand-in for the population's overall wellbeing within a nation. Front-line healthcare professionals will have increased access to information, including innovative techniques and best practises, for handling urgent health crises as Internet connectivity becomes more widely available in developing nations. Internet usage can also improve academic results as indicated by literacy rates. The HDI index incorporates these elements, making it a unique proxy for overall wellbeing.

The empirical study tests the hypothesis by contrasting the outcomes of fitting various econometric models to each sample. In order to account for or adjust for endogeneity resulting from the potential simultaneity issue of jointly determined dependent and explanatory variables, dynamic panel data and finite mixture model estimate techniques are used. A case for the causal effects of Internet use on economic outcomes can be made by accounting for the potential endogeneity of the measure of Internet use.

The use of the Internet may have a favourable impact on economic outcomes via a variety of processes. By reducing the distances between people, businesses, and nations and increasing information flow, access to the Internet lowers the cost of transactions and transportation. The sharing of knowledge and ideas is essential for the advancement of technology. According to Granovetter (2005), social networks have a significant impact on economic outcomes, particularly when it comes to supporting innovation. Websites that offer social networking features, like Facebook, are one of the fastest-growing types of Internet communication. Access to the Internet has expanded information availability, which could improve institutions' efficiency and transparency, resulting in greater governance. As Acemoglu et al. (2001) have demonstrated, better institutions can have favourable economic results. Kalathil (2003) makes a compelling case for how Internet use might promote effective governance.

By lowering search and transaction costs, information exchange increases market efficiency, which in turn can enhance demand, domestic production, and trade opportunities since it connects buyers and sellers and therefore expands marketplaces. New markets and industries can be created using the internet and other information technology. Access to educational resources via the internet can result in the production of additional human capital and an increase in labour productivity. Similar to this, access to health care is being made possible for people who might not have had it otherwise thanks to online health information. Economic development outcomes can be stimulated and amplified by these kinds of effects in economies at all stages of development.

Studies emphasising the ability of growing Internet use to modify society are starting to appear more frequently in the literature. In order to access new markets, learn new skills through shared experiences, and create more robust supply chains, small rural farmers in Central America and India can use ICT, according to a detailed analysis provided by Parikh et al. (2007). Advanced ICT networks encourage Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), which enhances economic opportunities in nations of all development levels, as Reynolds et al. (2004) show.

Although the effects will probably be favourable at all income levels, they will probably vary based on the countries' economic classes. Before many of the positive effects of Internet accessibility can have a large impact on the economy, developing countries must have basic public infrastructure, such as energy distribution, sanitation, primary care, and education systems. It's possible that low-income nations lack the political and social institutions needed for their populace to truly benefit from Internet access. High- and middle-income nations have attained levels of economic stability (they are higher on the Maslow's hierarchy of needs applied to economies pyramid) and are able to draw investment in the communications infrastructure, which can help educational systems operate more effectively and result in a population with a higher level of literacy.

In the context of this investigation, investing in Internet use can be seen as a complement to both investments in physical capital and human capital, as it makes workers more efficient by giving them access to knowledge that improves their skills and more rapid ways to create, disseminate, and assimilate information. The evidence in this dissertation shows that Internet use has a favourable impact on economic growth and other development outcomes, even if it does not give a growth story per se.

This dissertation's main goal is to present empirical proof of the causal link between rising Internet usage and rising economic activity across a spectrum of development outcomes. I use the per capita GDP, exports, the size of domestic equity markets, and overall wellbeing as assessed by the HDI as development indicators in this dissertation. Domestic developing economies will change when more people and enterprises in those areas start accessing the Internet. The way people learn about goods and services through websites and email will change how things are produced and consumed. A greater flow of information about available jobs, production methods, and new goods will make resource allocation and human capital deployment more effective. Although there are many development outcomes, I concentrate on these four in part because of their close connection to human welfare and in part because data are readily available.

Domestic markets that are expanding and mature draw consumers from other nations, enhancing trade prospects. Domestic equities markets become increasingly accessible to international capital markets, expanding the breadth and depth of the market's offerings as more economic agents from the public and private sectors establish online presences. The efficient operation of financial markets depends on information flow, which is crucial for developing equity markets. The usage of the internet has perhaps improved information production and distribution more than the use of the phone and fax machine combined. The effects of financial market structure and maturity on international Internet diffusion are examined by Yartey (2008), who discovers a strong correlation. This line of inquiry will be expanded upon in this dissertation in order to examine the effects of rising Internet usage on the size of the domestic equities market.

This dissertation shows that not all countries experience the same marginal advantages from Internet use. It depends on the specific outcome being researched whether increasing Internet access and Internet users in the least developed nations has a substantial impact on all aspects of economic development. All of the study's examined metrics of economic activity show a significant increase in middle-income nations as the number of Internet users increases.

The findings indicate that although middle-income nations have strong positive and significant effects, low-income countries exhibit lower, less significant effects of increased Internet use on exports and market capitalization. Middle-income nations see a rise in per capita export earnings of 2.3% as a result of a 10% increase in Internet users, but low-income countries see no change (fail to reject the null hypothesis of no change). The results are significant in terms of per capita GDP. Grows in per capita GDP of 3.2% in middle-income nations and even higher 3.5% in low-income countries are statistically significant when Internet usage increases by 10%.

Since Internet use has different effects on economic development outcomes depending on the country's income level, the policy recommendations must likewise differ. In low-income nations, increased Internet use has a strong positive impact on both the HDI average and per capita GDP. In order to provide Internet access at a reasonable cost, policymakers should concentrate on cellular phone networks. Additionally, foreign direct investment can be used to build the infrastructure required for increased Internet deployment while promoting foreign aid for health and education initiatives.

The effects of increased Internet usage are especially noticeable in nations with middle-income status. All four indicators of economic development in these nations are positively and significantly impacted by rising Internet usage. This argues that middle-income country policymakers should concentrate on giving the service industry institutional and legal support so that mobile banking, insurance, and other Internet-enabled technical solutions can be given to the populace via the mobile Internet. Widespread Internet connectivity is necessary for developing exports and domestic financial markets in nations with economies that are only starting to function and expand.

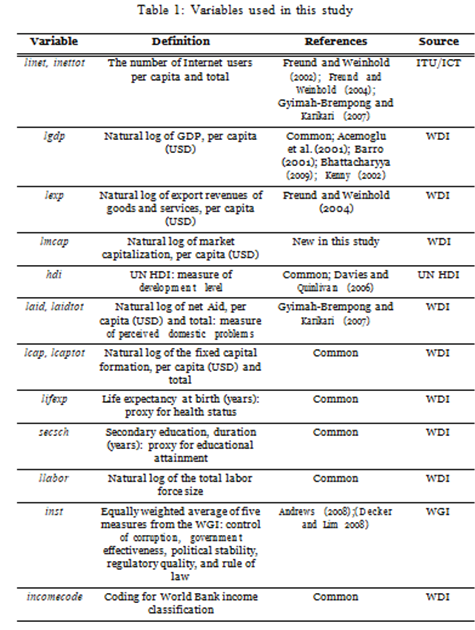

The rest of this dissertation is divided into the following sections: In order to comprehend the significance of this dissertation, Chapter 2 surveys the literature of pertinent earlier works on economic development, ICT, and economic growth. While Chapter 4 analyses the data sources and details the variables used for the empirical analysis, Chapter 3 presents the broad theoretical model and empirical technique for this study. The econometric findings of each investigation are presented and discussed in Chapter 5, and a summary, policy repercussions, and prospective future research possibilities are explored in Chapter 6.

1. Literature Review

Although there is a wealth of literature on economic growth, academic academics are just now starting to pay more attention to the connection between economic development and ICT. Existing research only offers a narrow and fragmentary perspective on the contribution that Internet use makes to economic growth. The literature has largely ignored other facets of development in favour of concentrating on the connection between information use and income increase. By examining many processes via which Internet use can affect the well-being of nations at various stages of economic growth, this dissertation offers a far broader perspective on the relationship between Internet use and development. The current research that serves as the backdrop for this dissertation is discussed in this section of the dissertation.

A foundation for understanding the contributions made by this study can be found in the numerous significant publications on the relationship between telecommunications generally and economic growth. While there are few published comprehensive empirical analyses of the role that Internet use plays on economic development, this study adds to a body of knowledge on this topic. I quickly highlight a few research that look at the connections between various facets of development. The review is organised into sections that examine how ICT impacts growth, factor productivity, welfare, trade, and equity markets, among other economic consequences.

1.1 ICT, Development, and Economic Growth

The methodology used in this study is an extension of the ground breaking research of Papakek (1973), which used cross-country panel methodologies to isolate the effects of FDI, aid, and exports on economic growth. It is also comparable to Barro's landmark study from 1991, which found a positive relationship between human capital and political stability, which in turn promotes economic growth. Before the advent of the Internet, there are outstanding evaluations of the state of empirical cross-country growth research by Levine and Zervos (1993) and later Sachs and Warner (1997). ICT, the Internet, or information mechanisms are not examined in these research' analysis of growth determinants. According to the enlarged Solow model-based neo-classical growth theory, long-term growth is reliant on technical advancement and labour force growth (Grossman and Helpman 1994). By examining how Internet use affects various outcomes, including economic growth, as a gauge of technical advancement, this dissertation adds to the body of scholarship.

Studies have just started to look into how important institutions are to economic growth. Although Rodrik et al. (2004) and Acemoglu et al. (2001) concur that institutional quality is a crucial component in economic development; neither study takes technological aspects into account that can improve productivity, trade, and the development of human capital. It is crucial to take institutional quality into account since it explains why technical advancement varies between nations. This dissertation isolates the effects of Internet use on development outcomes while controlling for institutional quality and other variables. It's interesting to note that Audretsch and Keilbach (2007) introduce the concept of entrepreneurship capital, or "the capacity for economic agents to generate new firms," as a crucial component of economic growth in Germany and discover that ICT infrastructure is a sizable component of entrepreneurship capital.

While this dissertation examines the effects of new technology (particularly, Internet use) on development outcomes by using institutions as a control variable, the research discussed above all employ institutions to explain differences in technical advancement.

The challenges faced by the world's poor people are depicted in great depth by Banerjee and Duflo (2007). Technology-based solutions are frequently advocated as a tool to help low-income people find ways to raise their income and raise their standard of living. In low-income nations, Gulati (2008) argues that investing in ICT infrastructure for educational purposes may primarily help the already wealthy, and that there may be a greater immediate need for fundamental educational services. By concentrating on potential distributional issues, Gulati's opinion ignores the total welfare benefit that ICT access and Internet use bring to the population of developing countries. It can be challenging to envision how relief programmes that give people access to ICT and the Internet will be of immediate assistance to a population that is already battling to survive. Although the poorest people of a population might not immediately gain from ICT use, overall wellbeing is increased. Redistributive measures can be put in place once welfare is increased to aid the poor.

Rajan and Subramanian (2008) use dynamic panel data approaches to further explore the issue of how foreign assistance transfers affect economic growth and come to the conclusion that aid transfers have little impact on growth across a range of nations. They employ a range of measurement techniques to control for endogeneity. To counteract this, Mishra and Newhouse (2009) found that, as measured by a decline in newborn death rates, direct economic aid does have a significant impact on health outcomes. In nations with underdeveloped health care systems, expanding access to information through ICT and the Internet will probably have favourable effects on health outcomes that may directly and indirectly affect economic development. In neither of these cases, the use of technology is the type of Internet infrastructure in particular and ICT infrastructure in general. Although economic aid is not directly examined in this dissertation, it serves as a crucial control in the empirical analysis and is viewed as endogenous.

In the mid to late 1990s, the increased accessibility to computers and Information Technologies (IT) in general started to have a revolutionary impact on industrialised economies. In their non-empirical study, DePrince and Ford (1999) concentrate on the economic growth that has resulted from the rapidly developing Internet economy in the United States and draw the following conclusion: "The emergence of the Internet economy is a Schumpeterian event that may rival the introduction of printing, steam power, the telephone, and the assembly line as a growth enhancing innovation." Madon (2000) acknowledges that the Internet will have significant societal effects in underdeveloped nations and offers a conceptual framework for comprehending how the Internet and economic growth interact. In poor countries, he argues that there are "six important application areas of the Internet, namely economic productivity, health, education, poverty alleviation and empowerment, democracy, and sustainable development." I am not aware of any published research that empirically investigate how using the Internet affects any of these factors. I experimentally research a number of Madon's hypothesised Internet-related effects on economic development with an emphasis on low- and middle-income nations as separate classes. Therefore, this dissertation offers the most thorough empirical analysis of the connection between Internet use and development that has ever been conducted in a single study.

The impact of telecommunications infrastructure on economic growth in Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) nations over a 20-year period is examined by Röller and Waverman (2001). They discover a significant causal effect of communications infrastructure on aggregate output after controlling for country fixed-effects and simultaneity. Despite the fact that this study concentrated on OECD nations, it's plausible that these effects exist in nations with various levels of development. In this study, I use government effectiveness as a proxy for institutional quality, which can affect the deployment of infrastructure.

Three distinct methods that ICT can increase economic output in developed economies are outlined by Jalava and Pohjola (2002). First, ICT products immediately boost production. Second, ICT capital is employed in the manufacture of different products. Third, the industries that produce ICTs themselves contribute goods and services. They show large productivity-enhancing effects of ICT in the United States in the 1990s using a macroeconomic growth accounting model, but weaker evidence in the other G7 nations. The effects are attributable to the US service sector's intense international competition. They don't try to look at the relationship in less developed nations.

Attempts to comprehend the slow economic growth rates in Africa and other low growth regions have been the focus of a lot of economic development study in the literature. The development literature hasn't typically focused on how ICT and the Internet might aid Africa's economic development. Even though the research of the effects of Internet use on developing economies is not primarily focused on Africa in this dissertation, the findings offer new information that can help in understanding the developing economies in Africa.

Ernst and Lundvall (1997) study whether new institutions may be required for developing countries to utilise cutting-edge IT solutions that may improve learning. Their stylized models are based on data from the United States and Japan. "For the majority of developing countries, the fundamental priority is to construct the essential institutions that provide incentives and externalities necessary for domestic learning," they propose understanding the impact of functioning institutions on economic growth in LDCs is made possible by significant studies like Acemoglu et al. (2001), Rodrik et al. (2004), and Banerjee and Duflo (2004). Using dynamic panel estimating approaches, Gyimah- Brempong (2000) discovers negative effects of corruption on growth in African nations during the 1990s. According to Kalathil (2003), having access to the Internet can aid in the formalisation of informal institutions and foster freedom in totalitarian regimes, which are frequently present in LDCs. It will be interesting to watch events in the Middle East and North Africa in 2011 to determine if the upheaval, sparked by communication over the Internet, results in more transparently operating institutions or if autocratic regimes just block Internet access to maintain power.

According to Decker and Lim (2008), political institutions play a key role in determining growth. These studies don't look into how communication affects institutions or how ICT influences income growth. The development and upkeep of efficient institutions depend heavily on the open flow of information. For instance, effective and responsible governance depends on both the open flow of information and transparency. Utilizing ICT and the Internet allows access to information that makes communication easier, and this information flow can only help institutions.

Czernich et al. (2009) examine the impact of broadband Internet infrastructure on economic growth in OECD nations in a recent study. They show the beneficial causal effects of more broadband Internet infrastructure in industrialised countries using a technology diffusion model and instrumental variable methodologies. Although there is no justification for limiting the application of this paradigm to just industrialised countries, the analysis is not extended to developing nations. The correlation between increased Internet bandwidth and economic growth in wealthy nations is highlighted by this result. The number of Internet users in poor nations might be viewed of as the sole indicator of ICT capacity. The direct impacts of increased Internet use on outcomes for development in underdeveloped nations are examined in this dissertation.

1.2 ICT, Internet, and Productivity

Numerous studies look into how ICT, IT investments, and information networks might increase productivity. Dedrick et al. (2003) give an extensive assessment of the literature encompassing fifty past firm and country level research on IT investment and draw the conclusion that IT investment significantly boosts economic growth and labour productivity. Other research have shown inconsistent results, notwithstanding Engel Brecht and Xayavong's (2006) conclusion that ICT does not definitely increase worker productivity in New Zealand. Using a stochastic-frontier production function estimation technique, Thompson and Garbacz (2007) discover that information networks, such as mobile and fixed-line telephones and the Internet, benefit both the "whole world" and some of the "poorest nations" by enhancing institutional functionality and business efficiency. In order to close the productivity and production gaps that exist between industrialised and developing countries, Stein Mueller (2001) draws the conclusion that investments in ICT may enable "leapfrogging" or "bypassing some of the processes of accumulation of human talents and fixed investment." The quick uptake and spread of cell phone networks to areas in developing nations with no history of fixed-line telephone infrastructure is one illustration of this leapfrogging. Ngwainmbi (2000) draws attention to the adjustments Africa must do in order to keep up with the technological advancements happening at the time of his study. Africa has to have access to energy resources and telecommunications infrastructure in order to compete in the global information industry. These studies, as well as numerous others, present evidence for the economic impacts of the Internet through casual observation, logic, and descriptive statistics. To better understand how the Internet affects economic development, this dissertation offers an empirical investigation utilising econometric techniques.

Goel and Hsieh (2002) argue that the Internet has the ability to increase competition and make markets more competitive by helping to eliminate information asymmetries, but they do not offer any empirical analysis to support their argument. Parikh et al. (2007) discuss how small-scale farmers might use a range of technical solutions to better integrate themselves into "global value chains," but they do so without offering any concrete evidence. Goyal (2010) demonstrates that when farmers are given access to information about market prices via Internet kiosks, rural soybean markets in India become more effective.

By enabling producers and consumers to interact and transact in novel ways, the availability of the internet can aid in the creation and expansion of markets. These studies offer convincing justifications for how and why access to ICT and the Internet might improve economic outcomes. The lack of micro level data in these investigations may be the cause of the absence of empirical proof. In order to remedy this vacuum in the literature, this dissertation uses aggregate country-level data to present empirical evidence of the effects of Internet use on economic development.

1.3 ICT, Internet, and Welfare

The body of knowledge about how ICT and the Internet affect societal well-being is growing. Both Crandall and Jackson (2001) and Prahalad and Hammond (2002) describe the large possibilities for commercial enterprises to profit from offering goods and services to rising markets in poor countries around the world, particularly by utilising ICT infrastructure. While it's possible that the poor areas of Chicago are not entirely comparable to developing nations, Masiet al(2003) findings that access to health information made the poor citizens of Chicago more powerful is an intriguing conclusion that might be equally applicable to LDCs. This dissertation makes an effort to investigate this link in the context of the developing world by looking at the effects of Internet use on several economic measurements and the UN HDI.

According to Jensen's fascinating and significant study from 2007, when Indian fishermen are given cell phones, price-dispersion in neighbourhood fish marketplaces is drastically decreased, improving both producer and consumer welfare. As a result, markets grow more effective as knowledge becomes more widely available. Using the internet is a useful way to spread information more widely. This is one of the ways that Internet use affects the state of the economy in developing nations.

ICT has a beneficial effect on advancing democracy and freedom of expression, according to Shirazi (2008), who examined eleven Middle Eastern nations. The widespread upheaval that occurred in North Africa and the Middle East in the early part of 2011 may be explained by the strong transformative power of populations connected through the Internet. Future research would be interesting in delving deeper into how institutions and corruption are affected by access to ICT.

Some researchers contend that ICT will have minimal effect on reducing poverty and promoting economic growth in LDCs using only reason and descriptive statistics. According to Kenny (2002), programmers shouldn't be used to create ubiquitous access to the Internet until it is made easier, less expensive, and literacy rates rise. His assertion that "LDCs appear ill-prepared to benefit from the potential that the Internet does present—they lack the physical and human resources, as well as the institutions required to leverage the e-economy" is reiterated (Kenny 2003). Kenny makes the claim that there is data showing that Internet use has little to no impact on the rate of income development in the lowest-income countries, but he does not conduct any actual research to support this claim. He contends that assisting with health, telephony, and literacy may benefit LDCs more than providing Internet access. In order to more fully explore these arguments, this dissertation extends them by examining the effects of the Internet using a thorough empirical study that isolates countries by income level.

Like Kenny indicates, Thompson and Garbacz (2007) show that expanding telecommunications networks improves organisational efficiency in nations of all economic development levels. More crucially, they clarify why the combination of institutional reform and growing information networks appears to help the poorest nations the most. This is probably a result of poor penetration, which raises the use of communications technology's marginal product. These findings support the study's central thesis, which holds that before the benefits of Internet accessibility can be realised, fundamental institutions and a strong social infrastructure must exist.

Chinn and Fairlie (2007) find that per capita income has a positive relationship with Internet use and raise the possibility of a simultaneity or reverse-causality issue with regard to income and Internet use by using "a technique of decomposing inter-group differences in a dependent variable into those due to different observable characteristics across groups." Neglecting this potential endogeneity will lead to skewed and contradictory empirical findings. This dissertation use dynamic panel data econometric methodologies and controls for the endogeneity concerns inherent in such cross-country empirical development research, whereas Chinn and Fairlie do not address the potential endogeneity problem. Chapter 5 provides a comprehensive description of the empirical findings.

Aker and Mbiti (2010) investigate the effects of increased mobile phone availability on the standard of living in Africa's low-income nations. They draw the conclusion that, despite not being an empirical study, the availability of mobile technology has the potential to advance economic development in sub-Saharan Africa. The potential advantages of expanding ICT accessibility to developing communities are explained by studies like this one, however they do not offer strong empirical support. This dissertation produces a thorough empirical examination where none now exists, so filling this gap in the literature.

1.4 Internet, Trade, and Investment

International trade, and more specifically exports, are one of the more well-developed fields of academic research on the economic effects of the Internet. Exports have a significant role in helping developing nations achieve rapid economic growth.

An analytical framework is provided by Feder (1982) for investigating the growth effects of exports on a cross-country panel of LDCs between 1964 and 1973. His findings imply that export-oriented policies help governments allocate resources more effectively and raise marginal factor productivity, which boosts economic growth in developing nations. Edwards (1998) examines the effects of economic openness (as determined by trade and policy indicators) on total factor productivity using a panel of 93 countries between 1960 and 1990. He discovers that economies with greater openness improve their production more quickly.

In a study concentrating on Canada and the United States, Zestos and Tao (2002) found causal correlations between the growth rates of exports and imports and the GDP of these two nations. This finding suggests that exports may be a substantial determinant of economic growth. Increased trade has been shown to significantly improve social welfare as evaluated by the UN HDI in a cross-country panel by Davies and Quinlivan (2006). It makes sense that Internet use would boost income growth through commerce if Internet use boosts trade.

Freund and Weinhold (2002) found that as Internet penetration rises in a nation, both import and export growth increase in the study of US trade in services. In particular, a 10% increase in Internet usage abroad is linked to a 1.7% rise in service exports to the US. In a later study on global trade (2004), they discover that having connection to the Internet—using Internet hosts8 as a proxy—helps to account for the expansion of trade. A 10 percentage point increase in the number of web hosts in a country causes around a 0.2 percentage point rise in export growth, according to this 2004 study's calculation of trade elasticity. They claim that using the Internet effectively eliminates transportation costs for services and reduces fixed costs. Both of these studies do not address potential endogeneity issues or focus on underdeveloped nations, thus they cannot draw any conclusions about causality. In this dissertation's empirical analysis of the effects of Internet use on exports, endogeneity is attempted to be controlled for utilising instrumental variables and dynamic panel estimating methods.

The study by Clarke and Wallsten (2006) aims to comprehend the extent to which the Internet encourages trade between industrialised and poor nations. Although they acknowledge that the direction of causality is ambiguous, their study reveals that having access to the Internet encourages exports from developing to developed nations. They provide a tool (a regulation dummy) for Internet users to account for this potential endogeneity, and they discover that their findings are unaffected by endogen zing Internet penetration. Using firm-level data from low- and middle-income nations in Europe and Central Asia, Clark's most recent work (2008) supports a causal connection between Internet use and exports and offers additional evidence of the high positive link.

To examine how FDI affects growth, Nair-Reichert and Weinhold (2001) used a panel of 24 developing nations using a mixed fixed and random effects estimate approach. They find evidence that growing FDI promotes growth in emerging nations, but the effects vary depending on the nation. This implies that research that presumes homogeneous effects could produce biassed results. This research investigates countries in sub-samples divided by socioeconomic level in order to examine the possibility of diverse effects on Internet use.

According to Choi (2003), there is substantial evidence that rising Internet usage encourages FDI inward. He argues that increased productivity as a result of Internet use makes the nation more alluring to foreign companies eager to invest. Choi makes no attempt to account for the possibility that FDI and Internet use could be determined concurrently or for the possibility that growing FDI could result in rising Internet use.

In their preliminary analysis of all nations from 1975 to 1998, Reynolds et al. (2004) found that information infrastructure is a significant driver of foreign direct investment. They employ the quantity of telephone lines as their infrastructure measure and apply a two-step residual estimator to try and account for endogeneity. Ko (2007) expands on this by utilising dynamic panel estimators and comes to the conclusion that rising Internet usage draws FDI when there are favourable network externalities in industrialised nations, such as reduced connectivity costs and new electronic markets. Negative network externalities like network congestion and rising Internet usage do not significantly boost FDI in developing nations. Ko's strategy of classifying nations into developed and developing samples is comparable to the strategy applied in this research. FDI is a key control variable in this dissertation's empirical investigation of how Internet use affects economic outcomes, even though the majority of research in the literature concentrate on the factors that influence FDI.

1.5 Internet and Equity Markets

The relationship between domestic capital markets and economic growth has been the focus of recent empirical research on equity markets in emerging nations. Levine and Zervos (1996) used cross-country panel methodologies to examine the impact of a market strength index on GDP growth and found indications of a positive association, but they were unable to establish a definitive causal link. In contrast, Arestis et al. (2001) used a vector auto-regression (VAR) framework to analyse five developed economies in order to investigate the connection between stock market development and economic growth. They discover that while stock markets may support global economic expansion, the banking sector has a higher overall impact. For the advanced economies under study, their findings imply that "bank-based financial systems may be more able to foster long-term growth than ones based on capital markets."

Bekaert et al. (2001) look into how the liberalisation of the financial sector affects the chances of economic growth in a sample of thirty emerging nations. According to their research, financial system liberalisation is linked to actual economic growth. These findings imply that there might be a connection between financial market size and economic outcomes, even if that was not the study's main aim. This dissertation investigates how Internet usage affects the size of the financial markets and makes the argument that the size of the capital markets is a sign of strengthening economic circumstances.

By defining financial globalisation as "the integration of a country's local financial system with worldwide financial markets and institutions," Schmukler (2004) expands on the concept. He argues that although financial globalisation might assist emerging nations, successful integration into the international financial system depends on robust institutions. The overall integration of developing nations into the global economy depends on their capital markets. This dissertation demonstrates how rising Internet usage can support the development of domestic equities markets, which in turn can support the acceleration of economic integration into the larger global economy.

Shirai (2004) examines the function of the domestic equities market and economic development in a thorough case study of China. He comes to the conclusion that China's market does not fulfil the requirements for supporting development because it falls short in three key areas: money raised from market issues is not used productively; state ownership is excessive overall; and questionable accounting practises render firm reports unreliable. This outcome might be a result of restrictions put in place by the Chinese government on the material that can be found online. Access to information is made possible via the Internet, and it is this open exchange of information that enables more effective resource and financial allocation.

Yartey (2008) finds that cross-country ICT diffusion is highly correlated with stock market development (measured by market capitalization to GDP) when investigating the factors influencing technology diffusion using a panel analytical technique. According to the report, ICT development funding is attracted to countries with substantial domestic market capitalizations from neighbouring ICT-enabled nations.

By demonstrating how rising Internet usage raises market capitalisation in developing nations, this dissertation offers fresh analyses to the literature. This could be attributed to the growing accessibility and transmission of information on domestic enterprises through Internet use, which piques the interest of foreign investors. Another mechanism might be the development of an appealing environment for new, tech-savvy enterprises that use domestic equity markets as a result of rising Internet usage.

1.6 Basis for this Dissertation

A foundation for understanding the contribution of this dissertation is provided by the research discussed in this succinct survey of the literature. These studies draw attention to the crucial connections between ICT, economic development, and economic growth that are made in this dissertation's investigation of Internet use and its effects on economic growth. This paper is the first comprehensive empirical investigation that offers a rich understanding of the causal relationship between Internet use and a diverse array of economic and welfare measures in developing countries, despite the fact that there are many academic studies exploring aspects of economic development and ICT.

2 Theoretical Framework and Estimation Methods

The two primary empirical techniques used to estimate the equations are presented in this chapter together with the theoretical framework that takes into account Internet use in a production functional form that can be used to investigate the relevant metrics of economic development. The theoretical framework is presented in the first section, and the estimating techniques are presented in the second.

2.1 Model Specification

Due to the ease of access, communication, and use of information offered by the internet, it has an impact on economic development. The efficient creation, improvement, and dissemination of information on the Internet has a variety of direct and indirect effects on economic development. Access to information can be used as a direct input to improve production decisions and labour and capital allocation. By lowering search and transaction costs and increasing export options, information can give businesses the chance to take advantage of economies of scale. The Internet offers a new mechanism for gathering and exchanging information that enables businesses to learn about new potential markets for finished goods and services, discover new inputs and production methods, and locate competitive prices for inputs that lead to more effective input ratios.

According to studies that have already been done, using the Internet to obtain more information increases both labour and capital productivity. Access to the Internet offers cutting-edge communication technologies like email and instant messaging that make the sharing of ideas easier. Knowledge is produced as a result of this information exchange, which is essential for technological advancement. Information therefore advances knowledge, which advances human capital.

I start with a country's production function, F, for an outcome Y, throughout period t, in a manner similar to the presentation in Barro and Salai-Martin (2004) that comes after Solow-Swan and Ramesy:

Yt = At · F (Kt, Lt, INETt, Xt) (1)

Yt is an economic outcome, At is total factor productivity (TFP), Kt is the capital stock, Lt is labour, INETt is the number of Internet users, and Xt is a vector of controls that might include a variety of elements, such as institutional policy initiatives. In this dissertation, I argue that Internet use, or INETt, has a favourable impact on the results of development.

∂Yt/∂INETt > 0. (2)

I model at as having both a deterministic and a stochastic component in accordance with what can be seen in the data. The stochastic component, ezt, produces random fluctuations around the trend growth path that are expected to follow an MA(1) process, whereas the deterministic component, egt, corresponds to an underlying trend with a constant rate of growth.

At = egtezt ; At > 0 (3)

where zt:

zt = ρzt−1 + t; t ∼ iid. (4)

As a result, egt+zt explain how technical advancements outside of the Internet behave.

This concept includes the consequences of both exogenous technological advancement and Internet use. Learning about new technology is made possible by having access to the internet. Additionally, having access to the Internet makes it easier for new technologies to be adopted and disseminated because it offers a variety of channels for discussing their training and uses, such as email, websites, online forums, and shared academic courseware.

ICT in general, and Internet use in particular, have been found to have a positive impact on economic production and factor productivity in nations at all levels of development to varied degrees, as can be observed from the earlier studies in the literature review. I build on this justification to investigate how Internet use affects a variety of outcomes related to economic growth.

Given that (1) lacks a clear functional form in economic theory, I take into account the widely-used Cobb-Douglas intensive (or per capita) type production function that takes into account the effects of Internet use, other technical advancements, and the vector of controls:

You'll see that this equation keeps a stochastic component and a trend component, gt component, zt. I model the trend and cyclical behavior as a time-invariant constant, α, plus the log of lagged realizations of the dependent variable, lnyt−1, and an iid stochastic shock, t:

gt + zt = gt + ρzt−1 + t = α + βlnyt−1 + t. (7)

Now substituting (7) into (6) and rearranging, I arrive at a log-linear model specifi- cation for an outcome yj, in country i, during time period t:

The major explanatory variable of interest in this generalised log-linear model specification is the number of Internet users in country I at time t, with coefficient. yjit is a specific per capita development outcome that is indexed by j, and inetit is now per capita Internet use. The lagged outcome variable lnyji, coefficient t1's is. Kit is the per-capita capital stock with coefficient, Xnit is one of the n row control vectors with coefficient, is the intercept, and it is a stochastic error term.

The variables in the vector X, which are defined for each equation, can change based on the specific development outcome being studied. The control variables are the same for three of the four models examined in this dissertation, though. This model employs log-linear models because the log transformation minimises the sensitivity of the resulting estimates to outliers and reduces the range of the data. Importantly, the log-log equation coefficients may be simply translated into elasticities, enabling direct comparison of the effects of Internet use on various outcomes of economic development.

In all of the estimation equations for each development outcome, the coefficient, on the measure of Internet users is of particular interest in this research because of its sign, magnitude, and statistical significance. In the presence of dynamics, the coefficient on the lag-dependent variable is anticipated to be positive, less than 1, and statistically significant. The elasticity of Internet use, will be non-negative with varying magnitudes and significance depending on the development outcome being researched and the specific sub-sample used, according to the study's premise.

he models used in the literature on economic development frequently use GDP as a function of the outcome under study. In this dissertation, I offer a general model specification that can be applied to empirical research on a variety of GDP-related economic development outcomes. As I view GDP as an economic development outcome measure that can be explained by the same controls as other measures, it is not included in this method as a control (for other outcomes). In fact, I think that this model's design might be helpful for investigating other development outcomes that I shall take into account in Chapter 6.

For the three per capita outcomes being examined here, the general log-linear estimating equation is:

lnyjit = α+βlnyji,t−1+γlinetit+δlcapit+ζ0laidit+ζ1secschit+ζ2lifexpit+ζ3instit+it. (9)

In this definition, lny is a logged per capita economic outcome that is indexed by j, linet is a measure of institutional quality, lcap is a natural log of per capita fixed capital formation, laid is a natural log of per capita net foreign aid, secsch is the length of secondary school in years, lifexp is a measure of life expectancy at birth, and laid is a natural log of per capita fixed capital formation. The variables chosen as controls are those that are frequently employed as proxies for the essential elements of economic development in growth and development empirics: fixed capital formation, foreign aid, education, health, and institutions. Since these models are estimating per capita results, there is no labour control.

Numerous empirical studies in the literature support the selection of control variables. At least since Pa- panek's ground breaking paper on the causes of economic development, controls for capital formation and aid have been in place (1973). Studies that include controls for human capital using educational attainment and health indices as proxies are common in the literature on economic growth. For instance, secondary education was taken into account in two important growth papers: Barro (1991) and Mankiw et al (1992). According to Sachs and Warner, life expectancy is a frequent proxy for health status (1997). Several significant articles have underlined the role of institutions in economic development, as was previously discussed in the literature review above, including Acemoglu et al. (2001), Rodrik et al. (2004), and Banerjee and Duflo (2004). Chapter 4 contains a detailed overview of the data sources and the particular control variables used.

The general model in (9) is followed by the log-linear model for logged per capita GDP, lgdp:

lgdpit = α+βlgdpi,t−1+γlinetit+δlcapit+ζ0laidit+ζ1secschit+ζ2lifexpit+ζ3instit+it

(10)

This approach differs somewhat from those frequently used in the literature for estimating the impact of ICT on exports. Typically, some measure of GDP is used as a control in empirical estimations of export growth. In this dissertation, I examine a variety of economic outcomes that are conditioned by the same variables as GDP. As a result, I apply the same model to estimate how using the Internet affects each of these metrics. Thus, the generic estimate equation (9) and the per capita GDP equation (10) above are both used in the log-linear model for per capita exports, lexp:

lexpit = α+βlexpi,t−1+γlinetit+δlcapit+ζ0laidit+ζ1secschit+ζ2lifexpit+ζ3instit+it

(11)

This expands on well-known models to investigate the impact of Internet use on exports.

The factors that influence capital markets in emerging nations have received scant empirical study. The majority of researches, as shown in the literature review, concentrate on financial markets as a predictor of economic growth rather than looking into the variables that influence financial market expansion. This dissertation introduces a novel idea: the size of domestic equities markets as an outcome of economic development. I contend that the same methodology that was used to examine other outcomes, like GDP and exports, may also be used to examine how the Internet affects market capitalization. The Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) was expanded by the theory of arbitrage pricing in order to investigate the numerous factors that affect the pricing of individual stocks. By extending this notion and incorporating it into existing models, such as those used by Holzmann (1997), Perotti and van Oijen (2001), and Bekaert et al. (2001), I aim to investigate the effects of Internet use as a determinant of market capitalization, conditional on a number of economic development factors. As a result, the estimation equation for market capitalization per person, or lmcp, is represented similarly to the equations above:

lmcpit = α+βlmcpi,t−1+γlinetit+δlcapit+ζ0laidit+ζ1secschit+ζ2lifexpit+ζ3instit+it

(12)

I anticipate that the coefficients for fixed capital formation, education, health, and institutions will all be positive for all three of the aforementioned estimate models. Although there is still discussion over the impact of help on economic growth, I predict a negative correlation because underperforming nations receive more aid. One of the endogeneity issues covered in the section below on estimation methodology is this one. With the exception of low-income nations, I anticipate that the Internet use coefficient in all equations will be positive and statistically significant across all economic strata.

The UN Human Development Index (HDI) is a composite index that takes into account a number of welfare indicators, including GDP per capita, adult literacy rate, and life expectancy at birth (United Nations 2008). From 1980 to 2000, it was calculated every ten years, then starting in 2005, the UN started calculating the metric annually. In order to fill in the data for the sample's missing years, this dissertation added interpolated HDI values. The HDI cannot be represented in the same way as the other equations since it is a mix of several different development indices.

Due to the structure of the index and the timing of the measurement, the model for estimating the effects of Internet use on HDI takes a different form. Although the HID's underlying components clearly exhibit dynamism, the index has historically not been monitored annually or at set intervals; instead, the measurement period has changed during the course of the index's development. As a result, the lagged dependent variable is not used in this model. As per capita control measures may result in skewed estimates because we lack the necessary data to reliably assess variables in terms of per capita, the HDI equation is log-linear and the controls are not. Here, the terms "linetto" (total Internet users), "lcaptot" (total fixed capital formation), and "laidtot" (total overseas assistance) are all expressed in current US dollars. A control for the size of the labor force, labor, is introduced in place of the proxies for health and educational attainment since those are factors in the index.

hdiit = α + γlinettotit + δlcaptotit + ζ0laidtotit + ζ1llaborit + ζ2instit + it (13)

I anticipate that the coefficient on in the middle-income sample will be positive and significant, much like in the estimate equations for GDP, exports, and market size. While those for aid and labour are predicted to be negative, the elasticity for capital formation and institutional strength are predicted to be positive.

The model specifications employed in this dissertation are aesthetically pleasing on first glance since they incorporate key components from significant growth and development empirical investigations. The purpose of these specifications is to examine the causal relationships between Internet use and various metrics of economic development activities. They adopt, adapt, and extend the common standards. I offer a consistent empirical framework for assessing the variety of economic development outcomes reported in this dissertation and others that will be investigated in the future by merging the key components of the model specifications from across the growth and development literatures.

2.2 Estimation Methods

In these models, there are two possible sources of endogeneity. They are the endogeneity of economic assistance and the direction of causality of Internet use. As people with more disposable income become more sophisticated in their demands for goods and services and businesses modernise using increased profits, rising domestic production and productivity, as measured by the per capita GDP, can undoubtedly lead to an increase in Internet availability and use. Similar to this, low productivity (low GDP per capita) will lead to increased help. In order to identify a causal relationship between Internet use and economic development, estimate approaches that take endogeneity into account are required by these models' sources of endogeneity. By addressing these endogeneity issues as well as the presence of dynamics, which complicates the application of the standard panel estimators, this research adds to the earlier development and ICT literature.

For empirical economic analysis, estimation using Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) is the standard starting point. It can offer accurate initial estimates of the marginal effects of the variables being studied. The equations can be stacked, and pooled ordinary least-squares can be used to estimate this model specification with ease. If the conditional mean is accurately specified, the errors are independent and identically distributed, and there is no multicollinearity in the regresses, OLS estimation can identify the parameters of interest. However, OLS estimation is biased and inconsistent when endogeneity and dynamics are present—when there is a correlation between the error term and any of the regresses—which is likely to happen in cross-country panels when examining aggregated macroeconomic measures because some of these measures are probably determined simultaneously. The aforementioned equations are dynamic because they contain lag dependent variables and potentially endogenous control variables.

Because the lagged realisation of the dependent variable is linked with the nation fixed-effects, using OLS to estimate (9) will result in issues. Both the lagged realisation and the country effect will be impacted by a shock to a country in the prior period. This goes against an OLS presumption. In the social science literature, temporally demeaning the data and then estimating the model on the time-demeaned data using OLS is a typical method for solving this problem. This method is known as a fixed-effects (FE) estimator. Since yit is correlated with it, the error term in the FE regression model, (it I will also be correlated with the response variable, (yit-yi), which is the same issue as with the OLS estimation. Fixed-effects estimates for each of the models are presented for comparison even though they do not solve the endogeneity issue.

More sophisticated econometric methods are required to account for the endogeneity contained in the model. Two more estimating techniques are applied in the empirical study in this dissertation using equations derived from (8). The first addresses Internet use and helps endogeneity and dynamism of the response variable by using Dynamic Panel Data estimation, the most common cross-country panel data estimate technique utilised in the literature. The second method examines the response variables as draws from a distribution made up of groups of unique continuous distributions of subpopulations using Finite Mixture Model estimation.

2.2.1 Dynamic Panel Data (DPD) Estimation

When dynamics and endogeneity are present, the Dynamic Panel Data estimators—more specifically, the Dynamic Panel System and Difference General Method of Moments (GMM) estimators—are frequently employed in the literature to estimate models on cross-country data. According to Bandyopadhyay et al., there are three reasons why these estimators are favoured (2011). The first step is to incorporate the long-lasting effects of Internet use into a dynamic framework. Second, there are significant endogeneity issues with regard to Internet use, financial help, and the metrics of development outcomes being taken into account. Two-stage least squares methods cannot be used without clearly defined and understood instrumental variables. Third, it's critical to account for unobserved national heterogeneity that can be linked to the outcomes of the study.

If we refer back to the general autoregressive model mentioned in equation (8) from Cameron and Trivedi (2005):

yit = α + βyi,t−1 + γlinetit + δkit + ζnXnit + it (14)

n

where the error term it is composed of ηi, representing time-invariant country specific e?ects, and uit, an idiosyncratic error that varies across countries and time periods:

it = ηi + uit (15)

with:

E[ηi] = E[it] = E[ηiuit] = 0 (16)

then the autoregressive model can be specified:

yit = α + βyi,t−1 + γlinetit + δkit + ζnXnit + ηi + uit. (17) n

The fixed effects (FE) and random effects (RE) models are the two frameworks that are utilized to account for i. While random effects, or between, estimation implies that I is a country-specific disturbance in each time period, fixed effects, or within, estimation assumes that I is a country-specific constant in the regression model. While the random effects approach implies that I is uncorrelated with X at all times, the fixed effects approach presupposes correlation between the unobserved heterogeneity and the regressors in X. When all explanatory variables are strictly exogenous, which is not the case in this situation; these panel estimating procedures produce estimates that are consistent.

It is necessary to use an estimator that generates reliable results even when dynamics and endogeneity are present. Dynamic GMM panel estimation methods that make use of the linear moment limitations implied by the aforementioned dynamic panel estimation equation have been introduced and extended by Arellano and Bond (1991), Arellano and Bover (1995), and Blundell and Bond (1998). Lagged differences of the dependent variables, endogenous regressors, and current values of strictly exogenous regressors are used as instruments in the DPD, an instrumental variable GMM estimator.

Since it can amplify gaps in unbalanced panels, the system DPD GMM estimator is preferable in this application over the difference estimator. This serves as the inspiration for the forward orthogonal deviations transformation (used in the estimation of the models in this dissertation), which "subtracts the average of all future accessible observations of a variable instead of the prior observation from the contemporaneous one. It is computable for all observations except the last for each individual, regardless of the number of gaps, minimizing data loss (Roodman 2006). In the presence of non-spherical errors, the two-step estimator is recommended over the less effective one-step estimator, and I choose the two-step form because I believe models with endogenous regresses and dynamics will have non-spherical errors.

The robustness of the obtained estimates is assessed using the common DPD statistical tests of over identification limits and serial correlation of the errors terms. Following the regression findings for each model in the appendices are tables with the test statistics.

2.2.2 Finite Mixture Model (FMM) Estimation

According to the World Bank's classification of countries by income, there are three distinct categories of development that can be identified: low, middle, and high income. In this dissertation, I make the assumption that Internet use affects countries differently depending on their level of economic development. This suggests that there may be some uniformity within each of the three distinct income classes that would enable a separate analysis of each income class. This estimate problem is ideally suited to use Finite Mixture Model (FMM) techniques since it is assumed that the distribution of outcomes under consideration is distributed into a finite number of reasonably homogeneous classes.

The FMM estimation technique assumes that the variable of interest is derived from a distribution that is made up of an additive mixture of distributions from several sub-populations or classes in order to model unobserved heterogeneity. FMM estimate is employed in various economic applications even if it is not yet widely used in development literature. In that it offers an alternative method of modeling heterogeneity, mixture modeling is appealing.

FMM estimation is used by Owen et al. (2009) to investigate the issue of country growth rates. They examine a number of latent class predictors, including models with two to five different classes and measures of latitude, settler mortality, and country landlocked status. They discover that, among the variables considered, institutional quality is the best predictor, and that a two-class model best fits the data. They come to the conclusion that country growth rate heterogeneity is ignored by single class pooled analysis. I propose that, contrary to their strategy, the latent class membership is determined by one's degree of income.

The identification of the precise, perhaps latent classes can be challenging without some natural interpretation, Cameron and Trivedi (2005) indicate, despite the fact that I have assumed a finite number of classes that account for country het- erogeneity. The latent classes have a theoretical foundation because they directly match to the World Bank country income classifications. This is because I am assuming that the effects of Internet use on economic development outcomes differ depending on the income level of the country.

The FMM estimate approach may model the various elasticity between income class even though it does not directly address endogeneity and dynamics issues. It models a different distribution for each class. Low, medium, and high income component densities are each represented by proportions c, where:

A probabilistic mixture of the densities from the three income classifications can be used to generalize the densities of the economic metrics in this study (or components.) This is represented by the equation below:

g (y | Θ) = π1g1 (y | Θ1)+ π2g2 (y | Θ2)+ π3g3 (y | Θ3) (20)

where gc (y | c) is the individual class density of the variable y given the parameter vector c and c is the percentage of the mixture density as defined previously. The following equation, where the mean of the distribution for the income class is discovered using equation (8), can be used to explain each distinct class density since each one is normal by construction:

This equation is not explicitly estimated; rather, the parameters for the means of the various class distributions used for mixing are provided by the linear estimation equations deriving from (8). The standard deviations, c, the regression coefficients, and the mixing probabilities can all change for each class when using this estimate method. Based on the income classification of each country, the model is estimated using maximal maximum likelihood estimation with set mixing probabilities.

The elasticity (or marginal effects), which are calculated at the means of the covariates indicated in the models, are then determined after the models have been estimated. Similar to how the coefficient estimates from the OLS and DPD estimators are interpreted, these values. As I anticipate finding a comparable sign, magnitude, and significance for the elasticity on Internet use regardless of the estimation method, using FMM to estimate each of the models provides a robustness check to the model parameters.

3 Data Sources and Panel Construction

A variety of socioeconomic variables are needed in order to conduct an empirical examination of the effects of Internet use on global economic development. To conduct this inquiry, data on Internet usage, macroeconomic indicators, institutional effectiveness of the government, and population health status are all required. The panel utilized in the empirical analysis had to be constructed from a variety of data sources.

This study focuses on the period from 1996 to 2007, which saw a dramatic increase in global Internet usage. There are two major reasons why this time frame was chosen. First, due to the low penetration rate of the Internet outside of a few wealthy nations, data on Internet use in general, and on low and medium income countries particularly, prior to 1996 are not generally available. Second, as of the date of writing, the data sources that are currently available only provide information on Internet usage for a wide number of nations as of 2007. Although there are some observations for 2008 and 2009 in the data used, most countries' data coverage is incomplete. Therefore, observations made after 2007 are not included in the economic projections.

The number of Internet users in a nation is the primary explanatory variable of interest for this study. The metrics for GDP, exports, assistance, and fixed capital creation are all expressed in current US dollars. All four of these variables are normalized by the population to obtain the per capita measurements. The life expectancy at birth in years serves as a proxy for health, while the number of years spent in secondary school serves as a proxy for educational achievement. Both the Institutional Quality Index and the HDI are indices that are used to assess the general wellbeing and quality of institutions, respectively. In the sections that follow, each variable and the specific data sets it was obtained from will be examined in detail.

The quality of the data available determines the robustness of any empirical research, and this study is no exception. Aggregated country level statistics are present in all the data sources used in this inquiry. Data that has been combined for each nation and year is relevant because this study examines phenomena at the aggregate country level. Undoubtedly, there is measurement error in these data, but since they are the main sources for cross-country panel studies in the economic literature, we rely on the supposition that the errors are random and not systemic and do not, thus, add bias into the samples.